Here’s why cutting disability benefits would be a huge mistake

There are worrying signs the UK government may go ahead with the previous government’s planned Work Capability Assessment (WCA) reforms – or impose similar changes which will reduce the support available to disabled people.

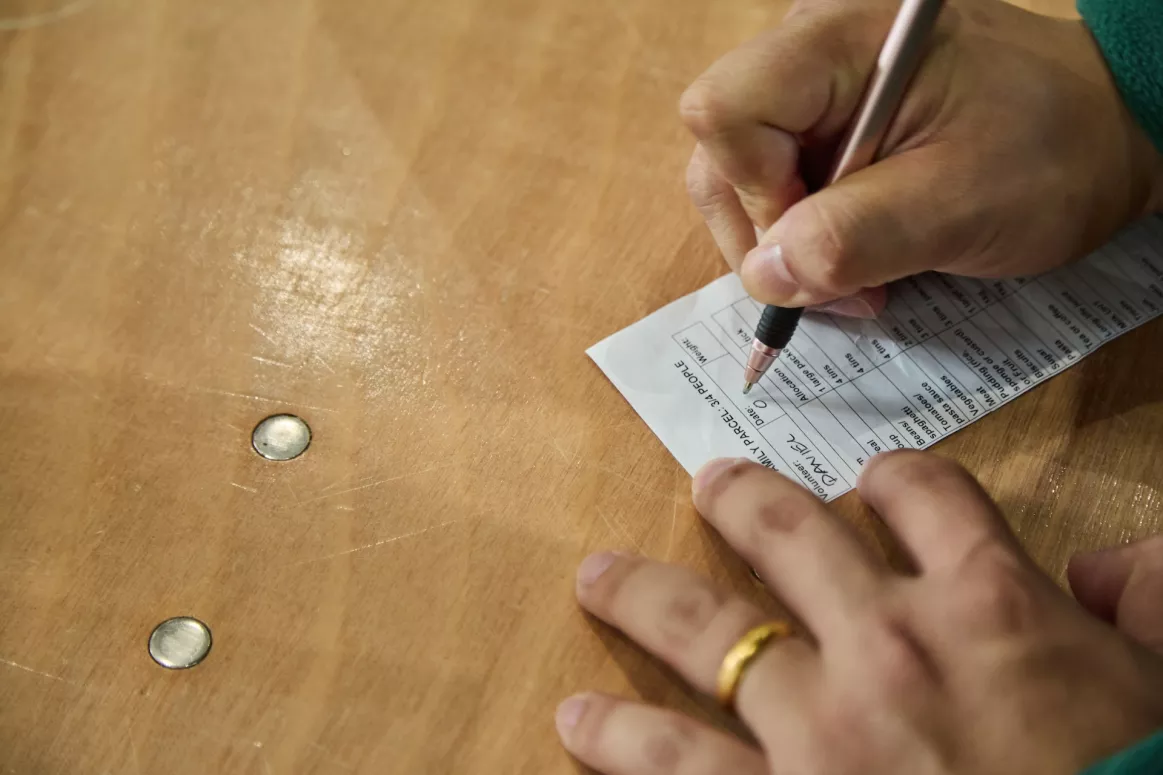

We know from the Trussell community of food banks, and what disabled people tell us, that changes that are at all close to the previous government’s plans would make already precarious financial situations impossible.

The previous UK government announced WCA reforms affecting sick and disabled people, which would limit eligibility for an additional payment in Universal Credit to people least able to prepare for, or enter, work (the ‘Limited Capability for Work Related Activity’ element) and increase job search requirements. These were expected to save the government around £1.3 billion a year by 2028/29.

The new government has indicated that they plan to go ahead with their own reforms to WCA, but given no detail as yet on how they will approach it. However, they have indicated that their reforms are expected to save £3 billion over four years.

If this is achieved through genuinely providing better employment support and access to healthcare so that people can access and sustain decent employment, it would be warmly welcomed by many. But previous experience tells us that such savings are more often achieved by simply cutting social security payments for people who still really need them.

Four big problems with WCA reforms that the new government must avoid

- More than 400,000 disabled people were expected to lose out on the LCWRA element by 2028/29 under the previously announced reforms, worth more than £400 a month. That’s a loss of nearly £5,000 a year for people who are likely to be least able to make up the shortfall through employment. When disabled people are already nearly three times more likely to face hunger than other people, and make up nearly seven in 10 people referred to our community of food banks, any reform which went in this direction would be a huge misstep.

- Increasing job search requirements while job-seeking rules (‘conditionality’) and work coach capacity remain unchanged risks exposing more disabled people to punitive sanctions. Work coaches are consistently overstretched. Concerns have already been raised by the National Audit Office about work coaches’ ability to support disabled people. Without safeguards, there’s a real risk of inappropriate job-seeking expectations which people simply cannot meet, resulting in sanctions. We know from recent history that sanctions have a clear association with food bank referrals; we should not be increasing this risk.

- The reforms were partly justified by the availability of remote working. Yet there’s limited evidence this helps disabled people on low incomes. Low-paid jobs – which people receiving social security are most likely to enter – are the least likely to offer flexible or remote working. We also know from our own data that digital exclusion is a real problem, undermining people’s ability to take up remote working. Over 40% of people referred to food banks in the Trussell community have no access to the internet at home; one in six have no access at all.

- The OBR forecast that just 3% of people affected would move into employment under the previous government’s plans, despite increasing employment having been stated as a key goal. We agree that work is vital for people and the economy, and the disability employment gap is a damning indictment of both support systems and the workplace. But pushing people into job-seeking and whipping away vital financial support is not the answer. These forecasts show this; the new government must not repeat this mistake.

A new agenda for change means correcting past mistakes

In response to the plans when in opposition, the Labour party recognised the importance of work, but declared, “This is not a serious plan. It is tinkering at the edges of a failing system.” They were right then; they would be wrong to go ahead with anything like a similar plan now.

We know the UK government is making difficult political choices on public spending. But we also know that ignoring investment in social security – or, worse, cutting social security – has its own economic cost. Our public services are already creaking under the weight of hunger and hardship. GPs and wider health services, schools – they see the cost of people going without the essentials. People will struggle to look for work if they’re worried about putting food on the table or running their medical equipment. We hear these experiences every day.

The government has said it plans to set out its own stall on WCA and wider social security reform. It was welcome to hear that the government is effectively putting the previous administration’s PIP green paper on ice. It should treat these WCA reforms likewise. The government cannot set out a new social security agenda for disabled people, as part of delivering its decade of renewal, by continuing with the errors of the past.

The Autumn Statement is a chance to show the urgent change we need to support people who can least afford to bear the burden of tough public spending choices. Our latest research found 9.3 million people are at risk of hunger and hardship.

Rather than persisting with this misstep, the UK government should look to making a positive step forwards in its plans for updating our social security system. It has affordable options. A priority should be to set a protected minimum floor in Universal Credit – a level below which payments should not fall. It would limit the amounts clawed back to repay debt and the benefit cap. It would pave the way for future reform. And it would show the government is serious about change.

We were promised change at the election – we need to see our government deliver.